Latter-day Saint scholar Hugh Nibley once wrote that the story of Enoch found in the Book of Moses “offers the nearest thing to a perfectly foolproof test—neat, clear-cut, and decisive—of Joseph Smith’s claim to inspiration.” Why? Because, unlike The Book of Mormon, we have actual ancient records about Enoch that we can use as a measuring stick against what Joseph wrote about Enoch. This article explores just one striking similarity between Joseph’s Enoch, and the Enoch we’ve come to know from ancient documents. I apologize in advance for how academic this is going to get, but when trying to answer the “How do we know this?” questions, academia is usually the answer.

Enoch and Mahujah

The Old Testament briefly mentions Enoch in Genesis 4 and 5. After that, he’s not mentioned until Luke 3 (and then only as one name in a looong genealogical list.) He shows up again in Hebrews 11, which casually mentions how Enoch was so righteous that he never died, but was translated. The final mention of Enoch occurs in Jude 1, which mentions one of his prophecies. Moral of the story: The Bible doesn’t tell us very much about this guy.

The Old Testament briefly mentions Enoch in Genesis 4 and 5. After that, he’s not mentioned until Luke 3 (and then only as one name in a looong genealogical list.) He shows up again in Hebrews 11, which casually mentions how Enoch was so righteous that he never died, but was translated. The final mention of Enoch occurs in Jude 1, which mentions one of his prophecies. Moral of the story: The Bible doesn’t tell us very much about this guy.

Joseph tells us much more. But this article isn’t going to focus so much on Enoch himself—we’re going to look at one of his associates that went by the name of Mahijah. He first shows up in Moses 6:40 of the Pearl of Great Price,

And there came a man unto him, whose name was Mahijah, and said unto him: Tell us plainly who thou art, and from whence thou comest?

In the next chapter of Moses, we see a variation of the name Mahijah show up again. But this time, it’s spelled Mahujah. Moses 7:2,

And from that time forth Enoch began to prophesy, saying unto the people, that: As I was journeying, and stood upon the place Mahujah, and cried unto the Lord, there came a voice out of heaven, saying—Turn ye, and get ye upon the mount Simeon.

Slight tangent: Is Mahujah a person or a place?

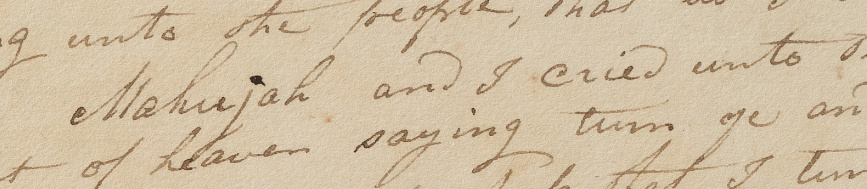

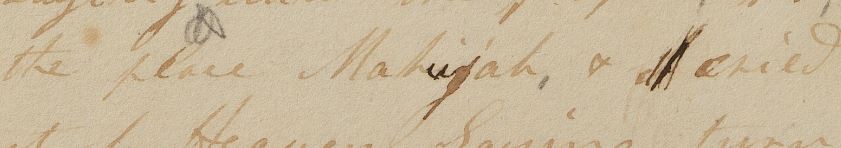

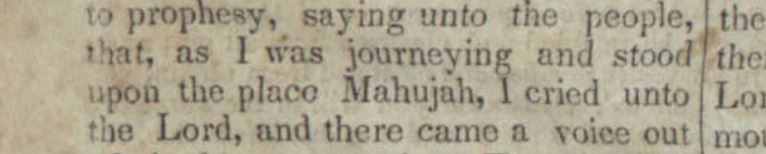

In our current edition of the Book of Moses, Mahujah appears to be a place. This isn’t a problem, because many places are named after people. Nonetheless, it may interest the reader to know that in the original manuscript of Moses 7 (part of Joseph’s translation of Genesis), the verse reads (emphasis added), “Enoch began to prophecy saying unto the people, that as I was journ[ey]ing and stood in the place Mahujah and I cried unto the Lord….”

However, by the second revision of the manuscript, a comma is added, and it appears the “I” is crossed out.

Yet, when Moses 7 made its first public appearance in the Evening and Morning Star in August, 1832, the comma was still included, but the “I” is also included, and the “and” is deleted.

The following quote from Robert J. Matthews is helpful:

Although the translation of the early chapters of Genesis was initially revealed and recorded between June 1830 and February 1831, it is clear that the Prophet Joseph Smith continued to revise and modify this material until his death in 1844.

But whether Mahujah is the name of a person or a place named after a person, how do we know Mahijah and Mahujah are both variations of the same name? We’ll get to that in a bit. Just give me the benefit of the doubt, for now.

Mahujah in the Bible

Mahujah also shows up in the Bible—Genesis 4:18. But this time it shows up as Mehujael.

And unto Enoch was born Irad: and Irad begat Mehujael: and Mehujael begat Methusael: and Methusael begat Lamech.

OK, but how do we know that Mehujael and Mahujah are the same name? Well, for two reasons. Bare with me here.

First, Hebrew doesn’t have vowels

The transliterated Hebrew word for Jehovah, for example, is Yahweh. But, since vowels don’t exist in Hebrew, the Hebrew word for Yahweh, in English letters, would simply be YHWH. All vowels are simply added in to help our English brains read. So, in the case of Mehujael and Mahujah, whether an e or a is used is largely a matter of preference. But there’s still another significant difference in the names to account for.

Second, El and Jah in Hebrew

Mehuja-el obviously ends in el. Mahu-jah obviously ends in jah. But as it turns out, both of these suffixes are common ways of associating a name with God in Hebrew.

El references God, or a god, in general (little g). Jah/Yah and Iah, on the other hand, are all ways to tie a name to Jehovah (YAHweh) specifically. For example, the name Elijah (EL-i-JAH) means “my God is Yahweh.” Daniel (Dani-EL) is another example, meaning “God is my judge.” Isaiah (Isa-IAH) means “Yahweh is salvation.”

Thus we see how the names Mehuja-EL (apparently meaning, “smitten by God“) and Mahi-JAH are both names associated with God, just using slightly different suffixes.

Now that you know about El and Jah, what other names can you think of that include those Hebrew elements? Michael, Gabriel, Israel, Samuel, Lemuel …

INTERMISSION—Let’s catch up, cuz my brain hurts

OK, so here’s where we’ve been thus far:

- The Bible talks about Mahujah.

- The Book of Moses uses two forms of the name: Mahujah and Mahijah.

And here’s where we’re headed:

- The Masoretic text of the Bible mentions both Mahujah and Mahijah.

- Joseph Smith would not have had access to the Masoretic text of the Bible.

- If Joseph Smith was a fraud, how can this Mahujah/Mahijah situation be explained? Was Joseph a lucky guesser or an evil genius?

The Masoretic text of the Bible

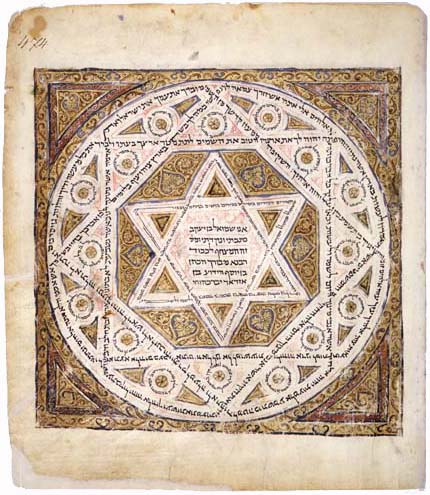

When we talk about the “Masoretic” text of the Bible, we’re talking about the oldest surviving Hebrew biblical records, which date back to about 1008 AD (as opposed to the Septuagint, which is the oldest Greek translation of the Old Testament). The original Hebrew texts (the Urtext) no longer exist (or we just haven’t found them yet). The Masoretic text largely consists of two records: the Leningrad Codex and the Aleppo Codex.

The Aleppo Codex was preserved in Near Eastern Jewish communities for hundreds of years before part of it was damaged in 1947. The Pentateuch, or first five books of the Bible, was damaged. And it wasn’t until 1958 that scholars started a serious study of the Aleppo Codex.

The Leningrad Codex (written in Hebrew) had been discovered prior to the publication of the Book of Moses, but it belonged to a Jewish manuscript collector named Abraham Firkovich. The Russian Imperial Library bought it from Firkovich in the 1840s. The next time the codex shows up in our history books is in the early 1900s, after it was used as a source-text for the Biblia Hebraica.

The point is: Joseph Smith simply did not have access to the Masoretic text of the Bible.

Where Mahujah/Mahijah shows up in the Masoretic text

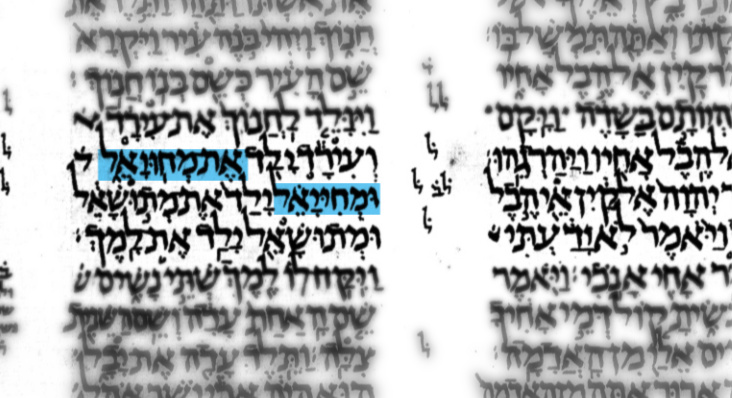

The following reference comes from the Leningrad Codex, probably due to the fact that Genesis may have been damaged in the Aleppo Codex. But no matter the codex, it’s still equally as impossible for Joseph to have acquired this information. So, where do Mahujah and Mahijah show up in the Masoretic text? Well, the simple answer is, right here:

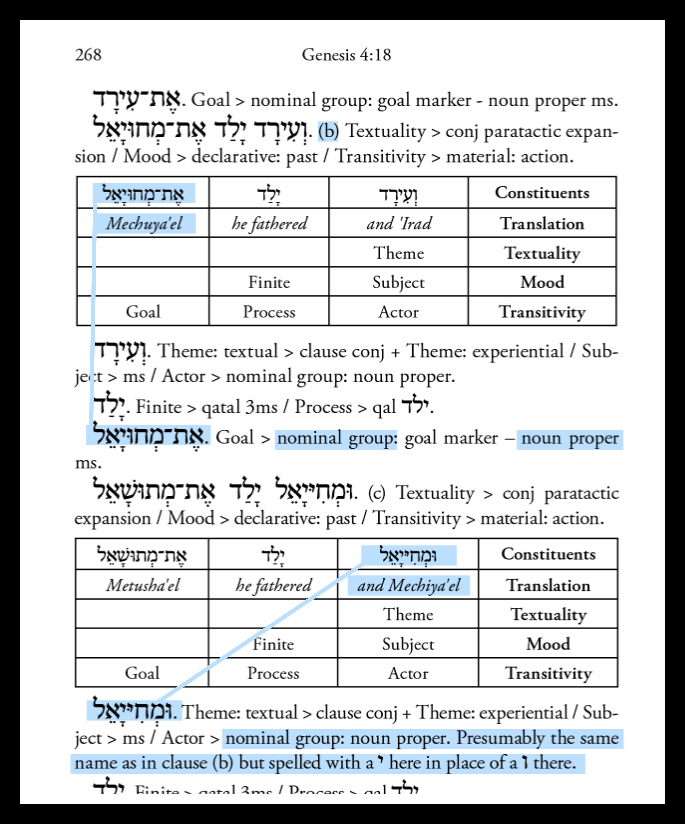

But, since that looks like a bunch of fancy gibberish to most people (myself included), I redirect you to page 268 of Genesis 1-11: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text, by Barry Bandstra. The excerpt that follows is also going to look extremely intimidating, but pay special attention to the bits I’ve highlighted and I’ll summarize the important bits afterward:

Moral of the story: In the Masoretic text, both Mahujah (Mechuya’el) and Mahijah (Mechiya’el) exist, almost back to back, in Genesis 4. As made evident by the highlighted text at the bottom of the image, these are two variations of the same name. In fact, in our King James Version of the Bible, the two names have been synthesized into one: Mehujael.

If Joseph Smith is simply drawing off of what he could learn from his KJV Bible, Mahijah should not exist in the Book of Moses (because it doesn’t exist in the Bible). And, technically, you’d expect Mahujah only to show up in the form expressed in the Bible: Mehujael.

And yet, the fact remains that both of the names Joseph uses in the Book of Moses are found in authentic biblical texts Joseph would have had no access to. Either Joseph was an unbelievably lucky fraud, or he was a prophet of God.

Bonus bit

Biblical text is not the only place we find the character Mahujah. He also makes an appearance in the pseudepigraphal Book of Giants in the form of Mahway or Mahaway. Again, Mahway may appear quite different from Mahujah, but they are both acceptable forms of the same Hebrew names. Not only does Mahujah show up in Book of Giants, but the role Mahujah plays in both stories (as one who questions Enoch) is also similar. This is a role not described in any biblical or apocryphal work available to Joseph Smith at the time. Book of Giants only strengthens Joseph’s prophetic claims.

For more information on this, check out the following resources:

A Strange Thing in the Land: The Return of the book of Enoch, Part 13

Ancient Affinities Within the LDS Book of Enoch Part Two

Could Joseph Smith Have Drawn On Ancient Manuscripts When He Translated the Story of Enoch?