-

Posts

26392 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

594

Everything posted by Vort

-

My granddaughters are being taught to sing by their mother. I sang to my children all through their childhood, but only a couple of them seem to have absorbed my interest in and captivation by song. I am not trained beyond high school choir and Church choir. My father had a truly beautiful voice, even untrained. I inherited his love of song, but not the beauty of his voice. I'm planning on developing that talent in the next life.

-

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

I don't disagree. I was not actually explaining why you should care; rather, I was explaining my view of why I think other people seem to care. -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

Yes. The current narrative, which is frighteningly enough widely shared among the Saints (!!), is that the Priesthood ban was instituted by Brigham Young because Brigham Young was a racist and had hateful feelings toward black people. If you suggest that Joseph Smith instituted the ban, that pushes the onus back a generation and threatens many people's rosy view of the Prophet Joseph Smith. For some bizarre reason, many Saints who would feel threatened by overt personal moral criticism of Joseph Smith don't mind at all when such criticism is applied to Brigham Young. However that may be, the evidence that Brother Brigham (a Yankee) considered racially black people to be children of God and subjects of salvation is much too overwhelming for any reasonable person to deny. The fact that President Young himself, in discussing the Priesthood ban, openly said that the ban was a temporary measure that would one day be lifted seems to be forgotten in the rush to judgment and condemnation. I stand with Brigham Young, and I stand against any who would suggest that he was "racist" or that his "racist motivations" were at the root of the Priesthood ban. I believe that the Priesthood ban was instituted by God for good and sufficient reasons, reasons to which I am not privy and on which I do not speculate. -

Aside from the obvious fact that he was assassinated just over halfway through his term, Kennedy was a remarkably lucky president. He was a politician through and through, and not the visionary leader he was made out to be. For example, his famous proclamation that America would land men on the moon and bring them back by the end of the decade was almost pure political theater, a statement that Kennedy himself did not believe. Not to refuse due credit to the man, but I think he has been given very distinctly rose-colored treatment in history, a treatment not altogether merited by his actions as president. La vie en rose.

-

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

For the record, I have not dismissed your explanations, certainly not condescendingly. I have little interest in the topic other than defending the integrity of the prophets, past and present. And our present prophet has asked us not to speculate on the issue. I personally understand his expressions and actions as a call to let sleeping dogs lie and quit picking at the scab, and probably several other trite expressions, as well. I fear this thread itself and many of my contributions to it and like threads violate the spirit, and perhaps the letter, of the prophet's and apostles' requests. For this reason, I think I will probably drop out of this type of thread now and (if I can discipline myself) in the future. -

I would call NK "Uncle Rico", but that would be insulting to the Dynamite family.

-

Trump appears to have more influence right now, when he's not even in office, than President Biden. I find that both hilarious and more than a little unsettling.

-

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

It's applicable in that you're insisting that those who reject a theory you propose must necessarily come up with a "better" explanation—"better" meaning more convincing to you. When they don't, you say that by default your explanation must be the most "logical" available, because, you know, where are the competing explanations? -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

I knew gravity was caused by gravity fairies! I knew it! -

For Harry Potter fans. Look at all of this analysis and reasoning, mechanically produced based on two relatively short prompts. It's pretty impressive to me. ********************* Within JK Rowling's Harry Potter universe: Can ghosts ever die or otherwise cease to exist? What is the difference between someone's ghost and someone's portrait? Could the ghost of a person carry on a conversation with a portrait of the same person? Would they two share the same "database" of memory? How can a ghost or portrait learn new information? Since each appears to be immortal, would this mean that each is an essentially eternal database of information with infinite capacity? ChatGPT said: ChatGPT In J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter universe, ghosts and portraits are two distinct forms of magical "imprints" of a person, and they operate under different magical principles. Here’s a breakdown of the key differences and how they relate to your questions: 1. Can ghosts ever die or cease to exist? No, ghosts do not "die" in the traditional sense, but they are not truly alive either. They are considered "imprints" of a person's soul, left behind at the moment of death due to unresolved fear of moving on to the afterlife. Ghosts are not subject to aging or physical harm, and they remain bound to the places they haunt. While there is no canonical evidence of a ghost "ceasing to exist" on its own, it is implied that they are stuck in this state unless some magical force, possibly beyond the scope of normal wizarding magic, alters their condition. In theory, the ghost could choose to "move on" if given the opportunity, but this is speculative since the series doesn't address it directly. 2. What is the difference between a ghost and a portrait? Ghosts are the result of a magical choice made at the moment of death, essentially a fragment of the person’s soul. They have their own will, agency, and a continuous experience of time. Ghosts can move about freely (at least within their haunting range) and react to new events as they happen. Portraits are magical paintings enchanted to behave like the person they depict, but they are not "alive" or truly self-aware. Portraits are created intentionally during a person’s life, often requiring magical preparation, and they act based on a preloaded "simulation" of the subject’s personality and knowledge up to the point of the portrait's creation. Portraits can learn new information and carry on conversations, but they do so more like an AI chat model than a living mind. 3. Could the ghost of a person carry on a conversation with a portrait of the same person? Yes, but it would be a very peculiar experience. The ghost would have its full consciousness and continuity of memory, while the portrait would have the knowledge and personality of the person as they were at the time of the portrait’s creation. If you think of the ghost as the "spirit" and the portrait as a "recording," then the ghost would have all the memories of their life plus all the experiences they have had since becoming a ghost. The portrait, however, would only know the things that were "programmed" into it or things it has learned since its creation. So, they wouldn't "share a database" of memory. The ghost would likely think of the portrait as a lesser version of themselves, while the portrait might recognize the ghost as its "source material." 4. How can a ghost or portrait learn new information? Ghosts learn through normal experience and observation. They can witness events, eavesdrop on conversations, and remember them like any living person would. Portraits are more limited. While they can be taught new information, it requires someone to tell them the information directly (like a user updating a software program). Portraits can also learn from talking to other portraits, as seen when Hogwarts' portraits relay information to each other. 5. Do ghosts and portraits have infinite capacity for information? No clear magical limit is ever stated, but here’s a reasonable interpretation: Ghosts might not have infinite memory, but they do seem to retain memories indefinitely. However, since they are "imprints" of a soul, their memories may be limited in scope or degrade over time. There’s no sign that ghosts have superhuman memory capacity. Portraits have a more limited form of memory, similar to a magically advanced AI. They may be bound by the amount of "intelligence" the enchantment allows. While portraits like Dumbledore’s seem to retain vast amounts of knowledge and continue to learn, it’s unclear if they have infinite capacity. Summary of Key Differences Feature Ghost Portrait Source Fragment of soul after death Enchanted painting Memory Continuously growing, real-time Static at creation, can learn Autonomy High (full agency) Limited (like AI) Movement Floats freely within areas Limited to frame, but can visit other portraits Mortality Effectively immortal Immortal as long as the canvas exists Personality Continuous since life Snapshotted from subject Learning Ongoing through experience Must be told, like input data Final Thoughts A ghost is essentially a "trapped soul fragment," while a portrait is more like a magical "AI copy" of a person. They are not linked or synced, and while both can learn, only ghosts have a continuous stream of personal experience. Portraits, however, are bound by their initial "programming" and need to be fed new information. So, while a ghost and a portrait of the same person could have a conversation, the ghost would likely find it a frustrating experience, as it would be like speaking with a snapshot of their former self. You said: Speaking of databases, the existence of spoken spells, existing in various (including ancient or dead) languages, seems to imply that certain sounds can be bound to magical outcomes, and that thes bindings are kept in some sort of permanent or at least very long-term magical database of sorts. This is an explanation, at least, for e.g. Hermione's insistence that "wingardium leviosa" be pronounced Just So. (Speaking of which, since Hermione seems to speak in a "received pronunciation" accent and used that accent in successfully casting the spell, and since RP was developed during perhaps the eighteenth century, that would suggest that the wingarium leviosa "binding" took place no earlier than that.) So to create a new magical spell is to create such a magical database binding. Is there an in-universe explanation for this, and/or for how such "binding" is managed? ChatGPT said: ChatGPT This is a fascinating insight into the nature of spellcasting in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter universe, and it raises some profound questions about how magic works, particularly regarding language, pronunciation, and magical "databases" or "bindings." While the Harry Potter books never explicitly describe the metaphysics of spell creation or the "database" concept, there are several clues that can help us piece together a plausible explanation. 1. The Nature of Spoken Spells: Why Pronunciation Matters Hermione's emphasis on proper pronunciation ("It's Leviosa, not Levio-SAH!") suggests that spellcasting is, at least in part, a linguistic process where specific phonemes must be perfectly articulated. This implies that specific sounds are "bound" to magical effects. But why? One possible explanation is that these sounds tap into a pre-existing "magical lexicon" or "magical database" that exists within the fabric of magical reality. Wizards and witches, through centuries of experimentation, discovered and "bound" certain effects to specific phonetic patterns. Consider the following points: Linguistic Consistency: Spells have Latin or pseudo-Latin roots, but they are often not classical Latin. Wingardium Leviosa is a pseudo-Latin hybrid of "wing" (English) + arduus (Latin, "steep" or "high") + levis (Latin, "light"). This hybridization suggests the magical lexicon is somewhat fluid. Globalization of Magic: Different cultures have their own magical systems. While Latin-based spells dominate European wizarding, other magical traditions (like those seen at Mahoutokoro, Uagadou, or Castelobruxo) likely have their own "databases" of magical sounds and actions. Fixed vs. Flexible: While some magical effects (like Accio or Lumos) appear to have fixed incantations, others (like non-verbal spells or wandless magic) suggest that the "linguistic binding" can be bypassed. Conclusion: The phonetic form of spells might not be "natural" but rather an artifact of wizard-created bindings. Wizards assigned specific syllables to magical effects in the past, and since these assignments "work," they have become canonical. This also explains the rigidity of the system — it is self-reinforced by magical tradition. 2. How Were These "Bindings" Created? If spellcasting relies on pre-defined phonetic triggers, the obvious question is: Who set them up, and how? Here are some theories: Ancient Spellcrafters: In the same way that programming languages have "keywords" that are linked to specific operations, ancient wizards may have created and "recorded" these phonetic keys as part of magical experimentation. Early wizards likely discovered magical effects through trial and error, then recorded the phonetic patterns that achieved the desired result. Spell-Creation as R&D: We know that new spells can be invented (Snape's Sectumsempra is an example). To create a new spell, a wizard must find the right combination of mental intent, magical will, and phonetic form to "bind" the spell. This might be analogous to a wizard submitting a "new record" to the magical database of spells, which is then accessible to any witch or wizard who utters the spell correctly. Magical Standardization: The existence of spellbooks (like The Standard Book of Spells) implies that magical "authorities" have codified successful spells. Just as dictionaries formalize language, magical institutions like the Department of Mysteries may catalog and maintain a "library of spells" that wizards then learn. Conclusion: Spellcraft may be a combination of experimental linguistics, ritual magic, and magical bureaucracy. Ancient wizards "registered" successful spells into a shared magical "network," allowing later wizards to tap into those same bindings. 3. Is There a Magical "Database" of Spells? If we conceptualize the magical system as a "database" of phonetic triggers, several questions arise: Where is this database stored? It might be an abstract, non-physical "field" within magical reality. Perhaps the very nature of magic itself includes this "spell registry" in a way that is analogous to how computers have a built-in command set. Alternatively, it could be tied to the "Magical Fabric" (akin to the concept of aether, or the quantum field in physics) where magical laws are embedded. How is it accessed? A witch or wizard taps into this "lexicon" whenever they cast a spell. The wand, acting as a magical interface, "queries" the lexicon using the incantation as input. The success of the spell depends on proper input syntax (pronunciation) and the wizard's magical will (intent). This would explain why wands and pronunciation matter so much. The wand is the terminal, the incantation is the query, and the magical lexicon (stored in magical reality) is the database. Is the database "centralized" or "distributed"? The "centralized" theory suggests that magic operates according to a universal magical field where the "spells" are stored and all wizards tap into it. The "distributed" theory posits that each wizard's personal experience with spells, memories, and magical essence allows them to "access" certain aspects of the lexicon on their own. Conclusion: The idea of a magical database isn't canonically explicit, but it fits within the logic of the universe. Spell words can be thought of as "queries" into this magical field, and a successful cast occurs when the query matches an entry in this field. 4. Does the RP Pronunciation of "Wingardium Leviosa" Mean It Was Invented Recently? If RP (Received Pronunciation) only became standard in the 18th century, does that imply that Wingardium Leviosa is a relatively modern spell? Not necessarily. Here’s why: Phonetic Drift: If the spell existed before RP, it would have sounded different. As pronunciation shifted, it’s possible that modern wizards had to adjust their phonetics accordingly, which is why Hermione insists on the "modern" pronunciation. The magical "binding" may recognize close approximations of the phrase rather than one single fixed pronunciation. Redundancy of Phonemes: It could be that the magical "binding" system allows for a "phonetic range" to activate spells. Much like Google can understand search queries despite typos, perhaps magic recognizes a range of possible pronunciations, but only within a certain threshold of accuracy. Hermione's correction may reflect a pedagogical technique rather than an absolute magical law. Conclusion: It is not necessary that Wingardium Leviosa was created in the 18th century. The pronunciation may have shifted to fit RP, while the "spell binding" may have been flexible enough to recognize the newer pronunciation. 5. Can Wizards Create Their Own Spells? How Do They Do It? Yes, new spells can be created. Snape invents Sectumsempra, and Fred and George Weasley invent various spells for pranks. This implies that "spell binding" is a learnable magical process. Here’s how it might work: Discovery: The wizard experiments with intent and phonetic utterances, attempting to match them to a magical effect. Binding: If successful, the wizard "locks" the effect to a phonetic string. This may involve a deeper magical process, akin to "programming" a new function in the magical lexicon. Registration: The spell, once successfully "bound," exists as part of the shared magical field. Other wizards can use it if they learn the proper phonetics and intent. This process is likely a mix of trial, error, and innate magical skill. Ancient spells like Avada Kedavra may be so old that no one remembers who first bound them to the lexicon. Summary of Key Ideas Magic may be structured as a "database" or "field" where certain phonetic triggers (spells) are pre-bound to magical effects. Early wizards created the "bindings" and modern wizards inherit them. The system works similarly to how programming languages define "keywords" for specific functions. The "query" (spell) must be pronounced correctly, and this is why Hermione insists on Leviosa, not Levio-sah. The creation of new spells involves discovering a phonetic combination that "links" with an effect, much like a programmer defining a new function in software. The magical system may have regional dialects, with different wizarding schools using their own "language bindings" for spells. Conclusion The idea of spells being stored in a magical "database" is a useful conceptual model. It explains why pronunciation matters, how spells can be discovered and "bound" by ancient wizards, and why spells persist across centuries. This system has strong parallels with modern computing concepts like databases, query languages, and even AI learning models. The linguistic, cultural, and magical layers of spellcasting all reinforce the idea that magic, like language, evolves but maintains a deep-rooted structure.

-

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

I never had issue with the essay. My objection is that you claimed (unless I'm misremembering) that the essay stated that Brigham Young instituted the policy, which I thought (and think) is not the case. The essay makes no such statement. -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

Hmm. Maybe this is an issue of semantics. I was expecting evidence that Brigham Young said, in effect, "I have decided (or it has been revealed to me) that black men of African descent shall no longer be ordained to the Priesthood." Instead, there is an "announcement" (which may have simply been an acknowledgement; this is my guess) that a policy was in place that blacks of African descent could not receive higher temple ordinances or be ordained—along with the explicit acknowledgement that this was a temporary restriction that would be removed at some future date, and the continuing teaching that all men (meaning people) of every race, including African blacks, were subject to salvation and exaltation based on obedience to God's commandments. The institution of a policy is the moment at which it begins being practiced, not the moment when it is publicly acknowledged. I realize that, ideally, these two should be the same, but they often are not. Apparently, they were not in this case. My question is, When was the policy instituted (and not merely acknowledged or even announced)? It appears that we don't know the answer to that question. The essay explains that there is no evidence that such a policy existed during Joseph Smith's lifetime, so we assume that the policy was formally instituted by Brigham Young. Which is fine; I have no objection to that. It sounds like good practice when understanding history. But the key word is "assume"; it is merely an assumption. To go from "We assume Brigham Young instituted this policy" to "Brigham Young, and not Joseph Smith, instituted this policy" to "Joseph Smith did not want this policy, but Brigham Young introduced it" to "Brigham Young and not Joseph Smith introduced this policy based on his [Brigham's] own opinion and/or understanding" to "Brigham Young was a vile racist who instituted a racist policy" is unwarranted at every step. -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

That does not say that Brigham Young instituted the ban. It says only that he (Brother Brigham) announced it in 1852. It is a reasonable conjecture that the ban was effectively in place before that time, perhaps as early as 1844 or before. -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

Whaaa...? I must have glided right over something. (Happens to me a lot, more these days than it used to.) I missed this, and in rereading the essay, I can't find it. Can you point out to me where the essay on Race and the Priesthood states that Brigham Young instituted the ban? -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

Just thumbs-upping your rant. I hate artificially boosted wordcount. I understand the perceived need for such, but that does not change my position by a millimeter. Say what needs to be said, as clearly as reasonably possible, and then move on (or shut up). -

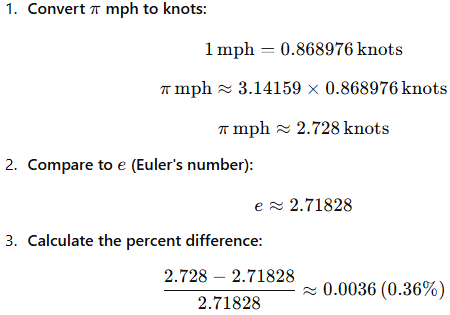

Here's one from yesterday that I thought was fun, based on a recent XKCD. ****************************************** True or false? To better than 1%, pi mph = e knots ChatGPT said: ChatGPT True. To better than 1%, the value of π miles per hour (mph) is indeed approximately equal to e knots. Here’s a quick calculation to see why: The difference is well under 1%, so the statement is true. You said: Take that, 22/7! ChatGPT said: ChatGPT Haha! Indeed — poor 22/7 thought it had the monopoly on π approximations. But here comes e knots, sneaking in with style and precision! Mathematical coincidences like this are oddly satisfying.

-

I have an admittedly weird fascination with LLMs in general and ChatGPT in particular. I fear I might come across as pedantic and boring, yes, in general, but specifically on this topic. But maybe others will enjoy sharing ChatGPT or other LLM exchanges. Here's one from this morning, with an apparent moral that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, a process is just a process, and a coincidence is just a coincidence. ******************************** Consider the following words that contain the "itch" letter combination, apparently exceedingly common in English words, and seeming to constitute a suffix of sorts: itch, bitch, ditch, glitch, hitch, pitch, stitch, witch. Also consider these other "itch"-related or -adjacent words: aitch (or haitch in some parts of Britain), a spelling of the phonetic pronunciation of the name of the letter H; britch, the back-constructed singular of the plural "britches", a variation on "breeches"; filch; kitsch; the name Mitch, short for Mitchell; niche (pronounced "neesh"); stretch and etch and other "etch" words. What's up with "itch"? It seems a strange construction, and even looks kind of weird, yet it's all over the place. What is/are its etymology/ies? ChatGPT said: ChatGPT The "itch" letter combination is indeed curious. It appears in several English words, but its origins are more varied than one might expect. Here's a breakdown of its etymology and usage across different words. 1. "itch" (as a word and suffix) Etymology: The word itch comes from Old English gycce (noun) and gyccean (verb), related to Middle Low German jukken and Old Norse juka, all of which refer to the sensation of itching or scratching. It is ultimately of Germanic origin. Usage: In words like itch, bitch, ditch, hitch, pitch, stitch, and witch, the "-itch" is not actually a suffix but part of a full root that happens to have converged into a similar form through various etymological processes. 2. Words ending in "-itch" Bitch: From Old English bicce (female dog) of Germanic origin, related to Old Norse bikkja (female dog) and German Betze (female dog). The "-itch" part is not a suffix but the natural evolution of the original Germanic form. Ditch: From Old English dic (a dike or trench), related to Old High German tih (pool, pond) and Dutch dijk (dike, embankment). The "tch" sound emerged through linguistic processes like palatalization, where the "k" sound softened to "ch." Glitch: A relatively modern word, appearing in the 1960s, likely from Yiddish glitsh (slip, slide) or German glitschen (to slip), with possible influence from electrical terminology. It is unrelated to the Germanic roots of other "-itch" words but still follows English phonological patterns. Hitch: From Middle English hicchen (to jerk, pull), related to Old English hician (to hiccup or gasp) and possibly to the concept of a sudden, jerky motion. Pitch: Two meanings and origins: (Tar-like substance): From Old English pic (tar, resin), ultimately from Latin pix (pitch, resin), through Proto-Indo-European roots. (Throw or toss): Possibly from Middle English pichen (to thrust, push) from Old English pician. Stitch: From Old English stice (a stab, prick, or puncture) and stician (to stab, pierce), related to Proto-Germanic stikiz (point, prick) and Proto-Indo-European steig- (to stick, prick). The "-itch" comes from the natural evolution of sound changes in Old and Middle English. Witch: From Old English wicce (female sorcerer) and wicca (male sorcerer), connected to the Proto-Germanic wikkōn (to twist, turn, or conjure) and perhaps Proto-Indo-European weik- (to bend, twist). The spelling evolved to "witch," but the "-itch" is not a suffix. 3. "Itch"-related or -adjacent words Aitch / Haitch: This is not etymologically related to the "-itch" words. It comes from the Old French ache, which was used to refer to the letter H. The "H" sound in French went silent, but the form ache influenced the English spelling "aitch" as the letter's name. The variant haitch is a later hypercorrection, likely by analogy with other letters like "bee" and "dee." Britch (as back-formation from "britches"): Breeches (or britches) comes from Old English bryċ (plural brēċ) meaning "garment for the legs," related to Old Norse brok and Proto-Germanic brōkiz (trousers, leggings). The "-ch" ending isn't an "-itch" but is related to the plural form ending in "-es," which sometimes produced this sound shift (similar to peach from Latin persicum). Filch: From Middle English filchen (to steal), related to Old English fylcian (to marshal troops) and possibly Old English feolce (band of people). Its similarity to "itch" is coincidental. Kitsch: A German loanword, borrowed in the 1920s, meaning "tacky art" or "lowbrow taste." The original German word kitsch is thought to derive from the verb kitschen (to scrape up dirt from the street) or from verkitschen (to sell cheap, second-rate goods). It is unrelated to "itch" words etymologically but aligns phonetically. Mitch (from Mitchell): A diminutive of Mitchell, which itself comes from Michael (from Hebrew Mikha'el, meaning "Who is like God?"). The "-itch" in Mitch is coincidental and comes from the phonetic shortening of the "ch" in Mitchell. Niche: From French niche (recess, cavity, nest) from Latin nidus (nest). The spelling and pronunciation shift is unrelated to "itch" words but follows a common English-French borrowing pattern, where "ch" can sound like "sh" (as in "chic"). Stretch / Etch: These derive from different sources but converge in form. Stretch: From Old English streccan (to stretch, extend), related to Proto-Germanic strakkjaną (to stretch) and Proto-Indo-European streg- (to stretch, spread). The "tch" evolved naturally from "cc" or "ch" sounds in Old English. Etch: From Dutch etsen (to etch) and German ätzen (to corrode or eat away), from Latin acere (to be sharp, sour). The "ch" reflects phonological conventions from Dutch and German, and the "-itch" similarity is accidental. 4. What's up with the "-itch" pattern? Palatalization and Sound Changes: Many words ending in "-itch" come from older words that ended in "c," "k," or "g" sounds. Over time, English underwent a process of palatalization, where hard "k" and "g" sounds before front vowels (like "i" and "e") softened to a "ch" or "sh" sound. This process happened in other Germanic languages, like Old Norse and Old High German, but it was especially prominent in English. For example: Old English dic → Middle English diche → Modern English ditch. Old English sticce → Middle English stiche → Modern English stitch. Borrowings and Coincidences: Some "-itch" words were borrowed directly from other languages (like glitch from Yiddish and kitsch from German) or came from proper nouns (like Mitch), but their endings coincidentally align with the phonological "tch" sound pattern. Not a Suffix: The "-itch" segment is not a true suffix but the product of multiple phonological shifts over time. English phonotactics (rules for allowable sound patterns) make the "tch" cluster common at the end of words. This same process can be seen in words like fetch, wretch, patch, scratch, etc., which do not have "-itch" but follow similar patterns. 5. Summary The "-itch" sound and spelling aren't the result of a suffix or a single linguistic process. Instead, they result from: Palatalization: Hard "k" or "g" sounds softened to "ch" in Old and Middle English (e.g., sticce → stitch). Borrowings: Words like kitsch (German), glitch (Yiddish), and niche (French) were borrowed directly. Natural Sound Evolution: Words like ditch (Old English dic) and bitch (Old English bicce) naturally evolved their spelling and pronunciation. The "itch" pattern is more phonological than morphological. It is a remnant of older sound shifts in English, reinforced by borrowing from other languages. Its frequency comes from convergent evolution rather than the influence of any singular suffix.

-

After watching that video, I wonder if I didn't suffer from the reverse of East Coast Bias. Maybe I just didn't see Ewing enough to realize what a monster talent he really was. It was obvious even to me that he was among the elite NBA centers at a time when NBA centers were dominant.

-

I actually thought at the time that Ewing was at least somewhat overrated. Today, I tend to think that Ewing was, not underrated, exactly, but probably underappreciated. The guy exemplified (and perhaps constituted) the blue-collar, lunchpail-toting wing of the elite NBA centers, occasionally flashy but consistently reliable, a true workhorse. He was the 5 version of Karl Malone's, and perhaps to some extent Charles Barkley's, 4. Such people were fun to watch, not so much because of their Jordanesque prowess, but because they Reliably Got The Job Done.

-

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

No conclusion can be reached without direct revelation on the topic. The best you can do is informed speculation. It should be identified for what it is, not called a conclusion. Your speculation is not unreasonable. This is far from saying it is a reliable narrative that should be forwarded. In fact, if it appears to contradict what our leaders have said or the direction they have chosen, it's certainly better to frame it as speculation, and probably not even push the narrative at all. Note that this is the case, even if the speculation later proves to be quite accurate. -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

I think you misspelled "the most reasonable speculation [IMO]". -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

In this, we do not agree. Joseph Smith doubtless said the above, and I expect he considered the idea of intermarriage between white people and black people to be objectionable, perhaps even repugnant. That was the common belief of his time. He may or may not have shared this belief, but he certainly supported the idea of drawing that societal distinction, as show in the above quote. However, your quote is misleading in that you put a period at the end, indicating the end of the sentence, when in fact the sentence continued. In full, the sentence read: "Had I anything to do with the negro, I would confine them by strict law to their own species and put them on a national Equalization." Read in the context of the rest of his quote, for which you provide the link, it's clear that Joseph Smith was not talking about preventing intermarriage between whites and blacks. Rather, he was stating as clearly as possible that black people of his time were a downtrodden, enslaved people, and that if they had the societal and educational advantages that white people of the time had—remember that Joseph Smith's own formal education was measured in weeks rather than years, so we're not talking about a high level of education—that they would do as well as the white people had done. (This was a remarkable statement for the time, something reminiscent of the things said by abolitionists. But while Joseph Smith clearly disapproved of slavery and proposed methods to abolish the abominable practice, he was no abolitionist in the political sense. Today we tend to think that abolitionists were these righteous, forward-thinking people acting with great integrity; but in Joseph Smith's time, abolitionists were considered a sort of extremist fringe group, even in the North. Later history would demonstrate that, in many instances, abolitionists like John Brown were not much more than domestic terrorists embracing extralegal means to enforce their own ideas. Think something like Antifa.) -

More evidence that the Priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith

Vort replied to Maverick's topic in LDS Gospel Discussion

As I have said before, I tend to agree with many of your scriptural interpretations on this matter. They are the traditional interpretations, but as (or more) importantly, they seem to me to be the natural reading of the verses. Those explanations that try to pooh-pooh the whole matter—arguing that ancient curses don't mean modern curses or, more often, that "darkness" or even "dark skin" doesn't actually refer to dermal pigmentation, but rather to some form of "spiritual darkness" that becomes visible in one's countenance—ring very hollow to me. Such things seem to me as grasping at straws in a desperate attempt to avoid racial implications in what would, at any other time and place in history, be considered the obvious meaning of words. (Anecdotally, one of the greatest supporters of the idea that some sort of premortal unworthiness or transgression was the motivation for the Priesthood ban—an idea of which I am not an advocate, just to be clear—was a marvelous African Church member in my previous stake. African, not African American; he and his wife had immigrated from an African country several years prior, and had had several children since arriving. He actually brought the issue up while we were chatting and sort of filled me in on his views. I was surprised that he was even familiar with the idea, much less that he agreed with it.) However, despite the idea that dark skin may have been a mark of a curse (or, as JAG has pointed out, more likely a mark of protection) in this particular case, dark skin per se was never the doctrinal issue. As time passed in the Restoration, it became increasingly clear that dark-skinned members of non-subSaharan African origin could participate in Priesthood rites such as temple endowments, and obviously the men could hold the Priesthood. So this doctrine was a ban on a specific, narrowed subset of "dark-skinned people". Full-blooded American Indians of various tribes could be very dark-skinned indeed (ironically enough, something seemingly explained in the Book of Mormon itself as a curse of sorts), yet there was never any doubt that American Indians, as children of Lehi and heirs to the covenants of their fathers, could hold and exercise the Priesthood. -

You don’t think it’s the ACC? With Duke, North Carolina, Virginia… What?! How DARE you!